方法与批判性思考

从路易斯康职业生涯的开始,他对每个设计过程都有一个“典型的”方法;这种方法在传统意义上并不常见,因为路易斯康的工作方式只有他自己独有。关于他的方法,1973年他说,“不管问题是什么,我总是从正方形开始。”从方形,路易斯康开始配置空间,基于他的依据:建筑’想成为’。他总是觉得自己有责任重新评估每一个任务书,不管预算如何,确定每个项目的核心,这是路易斯康作为一名设计师的过渡批判性倾向的产物,这种倾向导致了无数项目的流产。

功能与空间关系

如果有什么不同的话,路易斯康混合了气泡图,以一种遵循他的功能逻辑集群的方式定位所需的功能元素。建筑组织最重要的方面在于“服务”和“服务”空间之间的关系。

早期的住宅设计

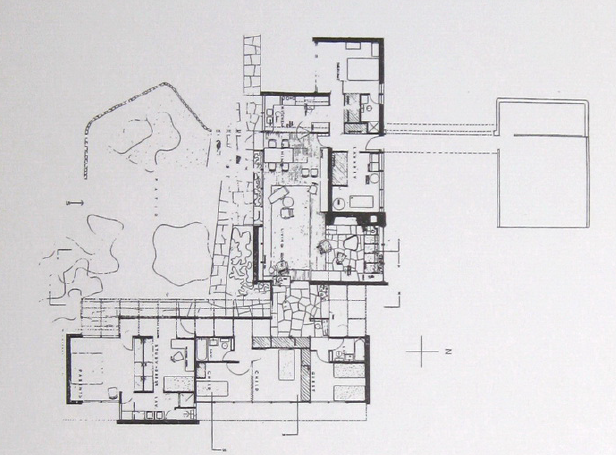

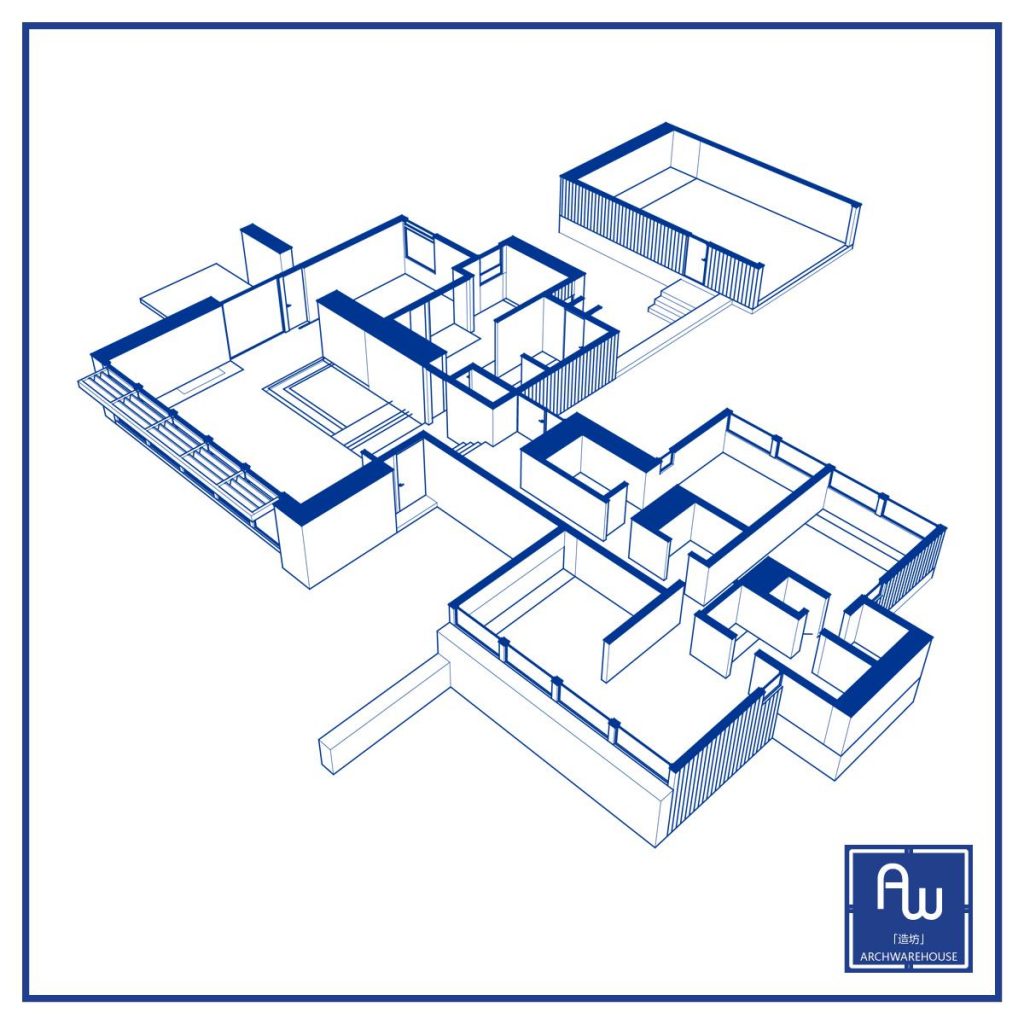

当回顾早期的住宅设计时,他对空间的优先次序和组织的演变变得显而易见。人们开始看到他的思维过程,从早期的方案开始,这些方案往往在形式上是独特的,但对路易斯康的空间组合是固有的。随着结构的发展,在特定的时期内,所有的布局都开始符合康的自己的语言。例如,20世纪40年代末的两项设计体现了路易斯康的早期方法和组织推理。 埃赫里住宅 Ehle House (1947-48)和 威斯住宅 Weiss House (1948-50)总结了他的时代设计的独特特点。结构的直线形式利用了相似功能的聚类,形成一对由过渡循环空间连接的体量。

埃赫里住宅和韦斯在平面上都是L形,上述相关功能的聚类导致了“居住”和“睡眠”体量的分离。虽然这两个住宅在组织和形式上是相似的,但后来的韦斯住宅的形式真正开始显示卡恩对“服务”和“被服务”空间的合理化。路易斯康以线性的方式布置空间,将生活和睡眠这两个立方体体块对齐在一起。体量由一个额外的服务空间连接,其中包含浴室和壁橱。虽然过渡空间——主要是入口和通道,带有一个完整的浴室——是两个体量之间的功能连接,路易斯康仍然对多功能入口空间的概念产生了兴趣。

正是在这一时期,路易斯康开始对他的住宅建筑采用双核计划——换句话说,两个不同的体量被分配的功能分开,卡恩称之为“生活”和“睡眠”。在此基础上,建立了两者之间的定向关系,并通过多功能入口将两者连接起来。在几乎每个实例中,体量和功能都是对应的。在费舍住宅(1960-67)对入口元素的使用表现出成熟和理解,他把它当作一个走廊,是一个体量的一部分,而不是两者之间的联系。这不仅是一个更有效的姿态,但它保持其实用性,同时和谐地集成两个并列的立方体。

然而,连接“连接节点”的过渡使用延续到了对理查德医学院(1957-64)的设计中,在这里,一组方形元素(在平面图中)通过伪节点连接成一个竖井。不知康使用这种手法“连接”与传统主义是否有任何表面上联系,或是否只是一个简单的解决方案缺乏任何历史决定论。可能康对形式的使用与历史上连字符的使用相似,只是作为分隔服务和服务空间问题的理性解决方案。从模块化的角度来看——尤其是像理查德这样的项目,它的形式有扩建的潜力——连接点的使用基于其简单和自由,非常有意义。路易斯康似乎开始理解过去和现在之间的联系,布朗利指出,“路易斯康强调,韦斯住宅大胆地使用了当地的石雕和未着色的木材,是当代的,但没有打破传统,每一个有思想的建筑师都会考虑到昨天有效和今天有效之间的连续性。

当从卡恩的职业生涯和全球建筑社区的角度来审视他的住宅设计时,特定同时代人的影响在他的作品中变得显而易见。正是这些影响与他自己对建筑和生活的看法的结合,帮助他形成了自己的建筑个性。从奥瑟住宅(1940年至1942年)开始,使用纹理木材和石头点缀现代主义主题,可以与乔治·豪(George Howe)的“方形阴影”(Washerman house)和一些柯布西耶的项目相比较。 埃赫里住宅 、韦斯住宅 和杰尼尔住宅 Genel House在两位包豪斯大师沃尔特·格罗皮乌斯和马塞尔·布鲁尔的指导下,展示了安妮·丁及其在哈佛大学的研究生教育对她的巨大影响。即使卡恩在20世纪50年代开始真正形成自己的风格,布鲁尔对丁格的影响和丁格对路易斯康的影响始终产生共鸣。布劳耶在盖勒住宅(1945)采用蝴蝶屋顶来打破立面的水平感,这似乎是路易斯康和泰恩在艾尔和韦斯住宅中模仿的。双核计划,也许是布鲁尔最常用的装置,不仅创造了“生活”和“睡眠”空间之间的界限,而且组织了体量,将室内和室外的生活空间融为一体。

From the beginning of Kahn’s professional career he had a ‘typical’ approach to each design process; the approach was hardly usual in the traditional sense, as Kahn worked in a manner native only to him. In regards to his method, he was quoted in 1973 as saying, “I always start with a square, no matter what the problem is.” From the square, Kahn would rationalize the spaces based on his justification that the programs would evolve into ‘what they wanted to be’. He always felt it was his duty to re-evaluate every program, regardless of budget, to identify the essential aspects of each project, a product of Kahn’s hypercritical tendency as a designer that led to the downfall of countless commissions.

If anything, Kahn hybridized the bubble diagram, orienting the desired programmatic elements in a fashion that followed his logical clustering of functions. The most important aspect of a building’s organization lay in the relationship between ‘served’ and ‘servant’ spaces; in terms of residential structures, the ‘served’ being bedrooms and living rooms and the ‘servant’ being the kitchen and bathrooms.

When one reviews Kahn’s early residential designs, the evolution of his prioritization and organization of spaces becomes readily apparent. One begins to see his thought process, beginning with the early schemes that are often unique in form but indigenous to Kahn’s rationalization of spaces. As the development of the structure progresses, the layouts all begin to conform to maxims native to Kahn during the specific period. For instance, two late 1940’s designs typify Kahn’s early approach and organizational reasoning. The unbuilt Harry Ehle house (1947-48) and the Morton Weiss house (1948-50) summarize the distinctive characteristics of his period designs. The rectilinear forms of the structures utilized a clustering of similar functions, resulting in a pair of volumes joined by a transitional circulation space.

Both the Ehle and Weiss houses are L-shaped in plan; the aforementioned clustering of related functions resulted in the separation of ‘living’ and ‘sleeping’ volumes. While both houses are similar in organization and form, the later Weiss house’s form truly begins to show Kahn’s rationalization of ‘served’ and ‘servant’ spaces. Kahn situates the spaces in a linear fashion, aligning the two cubic volumes – living and sleeping – beside one another. The volumes are connected by an additional servant space, which contains bathrooms and closets. Although the transitional space – predominately entry and passage, with a full bathroom – is a functional connection between both volumes, Kahn still appeared hung up on the idea of a multi-service entry space.

It is during this period that Kahn began to employ a bi-nuclear plan to his residential structures – in other words, two distinct volumes separated by their assigned functions, which Kahn termed ‘living’ and ‘sleeping’. From there, Kahn formulated an oriented relationship between the two and connected them by way of a multi-function entryway. In almost every instance, the volume is identical in its placement and use. Where Kahn appears to mature and understand the use of the entry element is at the Norman Fisher house (1960-67), where he treats it as a hallway that is a part of one volume rather than a linkage between the two. Not only is it a more efficient gesture, but it maintains its utility while harmoniously integrating the two juxtaposed cubes.

Nevertheless, the transitional use of the connective ‘hyphen’ continues into Kahn’s design for the Richards Medical Towers (1957-64), where a collection of square elements (in plan) are connected by pseudo-hyphens clustered into a single vertical shaft. It is unclear whether the traditionalism of the hyphen had any semblance of being within Kahn’s use of this connection, or whether it was simply a solution devoid of any historicism. Possibly Kahn’s use of the form was similar to the historic use of the hyphen, simply as a rational solution to the problem of separating served and servant spaces. From a modular standpoint – especially in regards to projects like Richards, which had the prospect of future additions built into its form – the hyphens make a lot of sense based on the simplicity and freedom of their use. It would appear that Kahn began to understand the connectivity between the past and the present, much in line with the theories of Cret.Brownlee notes, “Kahn insisted that the Weiss house, with its bold use of local stonework and untinted wood, was ‘contemporary but does not break with tradition.’ Citing the example of Pennsylvania barns in support of this position, [Kahn] argued that ‘the continuity between what was valid yesterday and what is valid today is considered by every thinking architect.’”

When looking at Kahn’s residential designs in the context of both his career and the global architectural community, the influence of specific contemporaries become apparent in his works. It was the combination of these influences with his own views on architecture and living that helped formulate his personal architectural identity. Beginning with the Jesse Oser house (1940-42), the use of textured wood and stone with interspersed Modernist motifs warrants comparison to George Howe’s “Square Shadows” (Washerman House) and a number of Corbusian projects (Fig. 1.9).40 The Ehle, Weiss, and the Samuel Genel house (1948-51) exhibit the strong influence of Anne Tyng and her graduate education at Harvard under two Bauhaus Masters, Walter Gropius and Marcel Breuer. Even as Kahn began to truly formulate his own style in the 1950’s, the influence of Breuer on Tyng and Tyng’s influence on Kahn resonate throughout.41 Breuer’s implementation of the butterfly roof at the Geller house (1945) to break up the horizontality of the elevation was seemingly mimicked by Kahn and Tyng at both the Ehle and Weiss houses. The bi-nuclear plan, perhaps Breuer’s most common device, not only created a delineation between ‘living’ and ‘sleeping’ spaces, but organized the volumes to integrate indoor and outdoor living spaces.

Pierson William Booher. (2009). Louis Kahn’s Fisher House: A Case Study on The Architectural Detail and Design Intent.Theses. University of Pennsylvania.