物体与织物

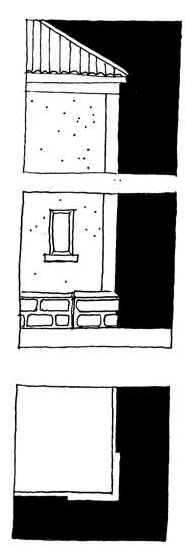

二十世纪都市化的一个根本问题是,它导致了物品的大量增加和对织物的忽视。有太多的建筑将自己呈现为“对象”,无视公众或他们在我们社会的价值观中所扮演的等级角色。原因可能有很多:公共卫生法律、宣传价值或职业虚荣心——但它们几乎不能作为未来应该遵循的道路的指标(图115)。随着构建对象的增加,它们作为异常的价值也随之降低。如今,规划规则和重复的生产方法赋予建筑一种对象状态,其内容和意义是普通的。这些建筑的重复与其说是与场地相适应的类型,不如说是几乎相同的模型。正是这样,现代建筑有时犯了罪,忽视了历史城市结构的教训。

A fundamental problem of twentiethcentury urbanization is that it has led to the multiplication of objects and the neglect of fabrics. There are too many buildings which present themselves as ‘objects’, indifferent to the public or hierarchical role they play in the values of our society. The reasons can be many: public health laws, publicity value or professional vanity – but they can scarcely be an indicator of the road that should be followed in the future (Figure 115). As building objects have multiplied, they have thus lost their value as exceptions. Nowadays, planning rules and repetitive methods of production confer an object-status upon buildings whose content and significance are ordinary. These buildings are repeated not so much as types adapted to the site, but as models reproduced almost identically. It is in this way that modern architecture has sometimes sinned, neglecting the lessons of the historic urban fabric.

奇怪的是,在建筑物内部还没有出现类似的现象。相反,从对物体的考虑到对空间的考虑,已经有了演变。矛盾的是,现代运动赋予了建筑客观的地位,赋予了室内织物的空间连续性(图116)。

Curiously there has not been a parallel phenomenon with the interiors of buildings. On the contrary, there has been an evolution away from the consideration of objects towards the consideration of space. Paradoxically, the Modern Movement has conferred upon buildings the object-status and upon interiors that of a fabric providing spatial continuity (Figure 116).

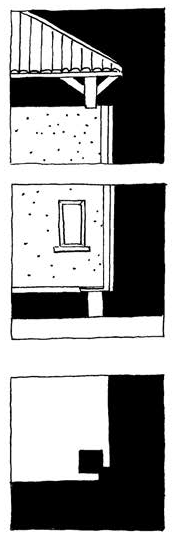

选择实物而不是面料的诱惑通常更大。后一种选择需要对环境有特别深刻的理解。另一方面,当建筑师最终收到委托,而客户可能正在建造他一生中唯一的一个项目时,往往会让他们的建筑脱颖而出。然而,我们不能把我们的城镇作为一个展示对象的集合来建造——这更像是用建筑办公室中积累的样本材料来建造一座房子。因此,让我们考虑网站和简要,并试图找出他们是否建议织物或对象;更常见的情况是,他们希望成为织物,因为这个物体,潜在的纪念碑,只有通过它的独特性和它对社区的重要性才能变得重要。关注城市肌理中的一针并不能减少任务的重要性,也不能减少发明创造的机会(图117)。

The temptation to opt for the object rather than the fabric is generally greater. The latter choice requires a particularly deep understanding of the context. On the other hand, the architect, when he eventually receives a commission and the client, who is perhaps building the only project of his life, tend to make their building stand out. However, we cannot build our towns as a collection of demonstration objects – that would be rather like building a house from sample materials accumulated in architectural offices. Let us thus consider the site and brief and try to find out whether they suggest fabric or object; more often they will wish to become fabric, because the object, the potential monument, can only become important by its uniqueness and its significance for the community. Concerning oneself with a stitch in the urban fabric does not by any means lessen the importance of the task nor the opportunity for invention and creativity (Figure 117).

因此,在他的方案中,建筑师必须掌握使他能够加强或减少建筑物的结构或物体特性的手段。面料的形式特征已经在“有序与无序”一章中讨论过,那些有助于物体感知的特征可以总结如下:

In his scheme, the architect must therefore master the means which enable him to reinforce or reduce the fabric or object character of a building. The formal characteristics of fabrics have already been discussed in the chapter ‘Order and Disorder’, those which contribute to the perception of objects can be summarized as follows:

物体是一个例外,一个打破规则的物体,一个孤立的物体,或者至少是一个物体与地面的连接。地面不是中立的。它将与物体处于一种平衡和紧张的状态。

The object is an exception, a breaking of the rule, an isolation or at least the articulation of a figure against a ground. The ground is not neutral. It will be in a state of balance and tension with the object.

圆形神庙是最优秀的对象建筑。它的完美的凸性,由于圆形计划,建立了它的隔离没有任何含糊。

The cylindrical temple is the objectbuilding par excellence (Figure 118). Its perfect convexity, due to the circular plan, establishes its isolation without the slightest ambiguity.

建筑物体

建筑是大量元素的体积组合。它们以更大的单元连接在一起,这些单元反过来又调节部分与整体之间的关系。由于建筑物是复合结构,元素之间的连接点被突出或淡化的方式产生了强烈不同的美学特征。一般来说,我们可以区分物体构成的两种方法:清晰度和连续性。

Buildings are the volumetric combination of a large number of elements. They are joined together in larger units which, in turn, modulate the relationships between parts and the whole. Since buildings are of composite structure, the manner in which the joints between elements are highlighted or played down gives rise to strongly differing aesthetic characteristics. In general, we can distinguish two methods of composition of the object: articulation and continuity.

历史上的某些时期有利于清晰表达,其它时期(更罕见的是)有利于连续性。哥特式时期的建筑艺术可能是两种方法结合最成功的一种。小圆柱群、适中的大写字母和拱顶的肋骨与一种铰接语言非常吻合。与此同时,柱子高耸的活力和延伸到肋和拱顶的活力,使得整体形式的连续性优先于部分的自主性。

Certain periods in history have favoured articulation, others – more rare – continuity. The art of building in the Gothic period is probably the one which has been the most successful in combining the two methods. The clusters of small columns, modest capitals and the ribs of the vaults correspond very well to an articulated language. At the same time, there exists enough dynamism in the soaring energy of the columns and their extension into ribs and vaults, that the continuity of the overall form takes precedence over the autonomy of parts.

巴洛克式教堂的内部以一种完全不同的方式利用了连接和连续性的双重作用。曲线和反曲线,壁柱和柱子,壁龛和凸出部分以连续的尺度连接在一起。清晰度是独一无二的;它是用来强调战略突破的;墙壁的集合,属于地球,天花板,拱顶和圆屋顶属于天堂。

In a quite different way the interior of a Baroque church exploits the double play of articulation and continuity. Curves and counter-curves, pilasters and columns, niches and bulges are linked together in a scale of continuity. Articulation is unique; it is reserved for emphasizing a strategic break; the meetings of the walls, belonging to the earth, and the ceilings, vaults and domes belonging to heaven.

构成的清晰性

元素之间的衔接强调了部分的自主性。它加强了不同组成建筑元素的特殊作用。这些中断形成重音和节奏,其位置、形式和大小应该在整体的考虑下进行。建筑逻辑是不够的,审美感性必须帮助建设。两个或几个元素之间的交会点用一个空或另一个专门为此设计的元素作下划线,如连接柱和柱顶的大写字母。很明显,在这个定义中,两个元素的简单“碰撞”仍然不能被认为是一种衔接。一个清晰的表达需要认识到这两个元素的限制和满足。我们创造一种表达的方式是多种多样的,可以同时发挥作用:材料的,建筑元素的,功能或意义的。与雕塑相反,建筑的表达需要参考上面列出的一种或几种方法:这不是一个反复无常的问题。表达使表达建筑、功能和与场地的关系成为可能。通过这种方式,建筑变得更加明确;它表达了自己的本质。

Articulation between elements accentuates the autonomy of parts. It strengthens the particular role of the different constituent building elements. The interruptions form accents and rhythms, the location, form and size of which should be carried out with the greatest care in consideration of the whole. Constructional logic is not sufficient justification, aesthetic sensibility must come to the aid of construction. The meeting point between two or several elements is underlined by a void or by another element specially designed to this effect, as for example the capital which articulates the column and the entablature. It is evident that in this definition the simple ‘collision’ of two elements may still not be considered as an articulation. An articulation requires a recognition of the limits and the meeting of the two elements. The means by which we can create an articulation are various and can come into play simultaneously: of material, of architectural element, of function or meaning. Contrary to sculpture, articulation in architecture requires a reference to one or several of the means listed above: it cannot be a question of caprice. Articulation makes it possible to express construction, function and relationship to the site. In this way the building becomes more explicit; it expresses its own nature.

构成的连续性

元素之间的连续性或“融合”降低了部分的自主性。它反映了整个物体中最大的元素。连续性以形式的渐进转变取代了元素的相对自主性。由此产生的形式包含潜在的感官享受类似于人体。它诉诸于触觉。连续线条的每一次波动都暗示着即将发生的事情。然后,该物体似乎是由一个单一的模具。例如,大型钢筋混凝土外壳就是这种情况。通常情况下,建筑的现实比它看起来更复杂,就像在当地的村庄里一样。在这种情况下,它是一个面,减少或消除了元素之间的连接处,创造了体量、轮廓和表面的连续性。实现这种连续性是一种技术上的壮举。连续性的使用当然有加强物体连贯性的好处。雕刻家经常使用这个装置,通过限制关节的数量到战略位置。以连续性为基础的当代建筑很难被接受。所举的例子很不寻常。原因可能是文化方面的。几个世纪以来,我们已经习惯了由铰接结构组成的城镇的结构和理性,我们很难想象它是用粘土建造的。这些连续的结构像奇怪的物体一样突出。

Continuity, or ‘fusion’ between elements reduces the autonomy of the parts. It reflects the largest element of the whole of the object. Continuity replaces the relative autonomy of the elements by a progressive transformation of form. The resulting form contains potential sensuality similar to that of the human body. It appeals to the tactile sense. Each undulation of the continuous line hints at what is to come. The object then appears to have been formed from a single mould. That is the case, for example, with large reinforced concrete shells. Often the constructional reality is more composite than it appears, as in the vernacular villages of the Cyclades. In this case, it is a facing which reduces or eradicates the joints between the elements and creates a continuity of volumes, contours and surfaces. Achievement of this continuity is something of a technical feat. The use of continuity certainly has the advantage of reinforcing the coherence of the object. Sculptors regularly use this device by limiting the number of articulations to strategic places. Contemporary building based on continuity has more difficulty in being accepted. The examples presented are unusual. The reasons may be of a cultural nature. Having been accustomed for centuries to the constructional and intellectual rationality of the town consisting of articulated structures, we have great difficulty in imagining it modelled in clay. These structures of continuity stand out like strange objects.

形体的边角与天地的关系

强化的边角

虽然物体之间的横向关系可以自由解释,甚至可能是一个无关紧要的问题,但建筑与地面的结合是不可避免的。它表明这些物体与我们同在,与我们同在地球上,与天空分离。然而,两者之间并非只有一种可能的关系。建筑物能给人一种“从地面上跳起来”、“沉入地下”、“被放置在地面上”或“悬浮在地面上”的印象。一个人如何选择并实施这些表达形式中的一种或另一种?

Whilst the lateral relationships between objects can be open to free interpretation, and may even be a matter of indifference, the meeting of the building with the ground is inescapable. It indicates that these objects are amongst us, with us on the earth, detached from the sky. There is not, however, only one possible relationship. A building can give the impression of ‘springing from the ground’, of ‘sinking into the ground’, or being ‘placed on the g r o u n d ‘ or ‘ h o v e r i n g above the ground’. How does one choose and put into effect one or other of these forms of expression?

突出的边缘,或凸出的一角,是赋予建筑这一特色特殊地位的标志。例如,基石经常被强调。它们不仅是建筑的标记和稳定元素,而且它们的处理也强调一个面的结束和另一个面的开始:基石属于两个面的。它们告诉我们墙体的厚度和稳定性,并为每个面提供一个横向框架。这种经典的方法从砖石建筑开始就被用在建筑物上,有时采用墙角壁柱的形式,更小心地处理墙角,或在粗糙的铸件上涂上简单的装饰。在所有这些情况下,角落的重要性被认识和描绘出来。

The accentuated edge, or corner in relief, is an indicator which grants a privileged status to this feature of the building. Cornerstones, for example, are often emphasized. They are not only markers and stabilizing elements for construction, but their treatment also emphasizes the end of one face and the beginning of the other: the cornerstones belong to both faces. They tell us about the thickness and stability of the wall and provide a lateral frame to each face. This classic method has been used on buildings since the beginning of masonry construction, sometimes taking the form of a corner pilaster, of a more careful corner treatment, or a simple decoration painted on the rough-cast. In all these cases the importance of the corner is recognized and delineated.

基座属于底面

在基座的帮助下,与地面相关的连接是第二个经典原则。它庆祝了一个简单的几何形式的建筑与不规则的地面的结合。一个非常稳定的中间元素为建筑提供了一个座位。建筑在一个精确的位置扎根:你不能像桌子上的玻璃一样“移动”它。因此,帕台农神庙的地基是属于地面的,而不是属于建筑的。此外,它必须接收和准备建设。基座有两种依赖关系:一种是与所支撑的物体有关,这种物体的构成必须是具体而精确的;在古典建筑中,同样的基座也适用于其他类似的情况。

Articulation in relation to the ground, with the aid of a plinth, is a second classic principle. It celebrates the meeting of a building of simple geometric form with the irregularity of the ground. An intermediary element of great stability provides a seating for the building. The building puts down roots in a precise location: one cannot ‘move’ it like a glass on a table. It is for this reason that the base of the Parthenon belongs to the ground, rather than to the building. Moreover, it must receive and prepare the building. The plinth has a double relationship of dependence: one relative to the object supported which must be specific and precise in its composition, and the other relative to the junction with the ground which is ineluctable and more generic; in classical architecture the same plinth is applicable to other similar situations.

基座融入建筑

第二种方法是将基座的概念,或者更确切地说是基地的概念,融入建筑本身,包括整个或部分底层。在 维也纳的斯坦霍夫教堂 中, 奥托·瓦格纳 纳采用了自文艺复兴以来一直流行的主题,标志着原始的泥土和高度精炼的建筑之间的过渡,包层采用了更质朴的处理,让人想起粗糙的泥土和岩石。在这种情况下,整个一楼都接受了这样的处理,就像在阿尔贝蒂的鲁塞莱宫,“高贵的钢琴”位于地面以上一层,粗糙的底座不适合它。但奥托瓦格纳进入他的建筑在上部的基地,同时增加了下半部分的乡土。

A second method consists of incorporating the idea of the plinth, or rather of the base, into the building itself by including the whole or part of the ground floor. In the Am Steinhof church (Figure 137) Otto Wagner takes up a theme that has been current since the Renaissance, by marking this transition between the raw earth and a highly refined building with a more rustic treatment of the cladding, reminiscent of the coarseness of earth and rock. In the cases where the whole of the ground floor receives this treatment, as in Alberti’s Palazzo Rucellai, the ‘piano nobile’ is located one floor above ground level, the rusticated base not being a suitable place for it. But Otto Wagner enters his building in the upper part of the base, whilst increasing the rustication of the lower part.

没有底座,直接接地

所选的例子可能导致错误的结论,即基座或底座总是一个重要的因素。事实并非如此;如果它是一个简单的建筑,识别与地面的连接处可以是一个适中的轮廓,甚至可以更精确地处理一条地面。

The examples that have been chosen could lead to the erroneous conclusion that plinth or base is always a substantial element. This is not so; if it is a simple building, the recognition of the junction with the ground can be a modest profile, or even the more precise handling of a strip of ground (Figure 138).

屋顶

屋顶上的檐口和屋顶处理雨水与需要保护的垂直面和开口之间的微妙过渡。它通常属于建筑,而不是天空,因此避免了视觉上的模糊,否则会导致明显的垂直延伸。根据建筑的重要性,这个上层终端可以包括整个顶层。在一些特殊的情况下,向天空的无限延伸成为一种追求的象征。

Capping with a cornice and a roof handles the delicate transition between the rainwater on the roof and the vertical faces and openings which need protecting. It generally belongs to the building and not to the sky, thus avoiding the visual ambiguity that would otherwise result from apparent verticle protraction. According to the importance of the building, this upper termination can include the whole of the top floor. There are some exceptional cases in which the extension towards the infinity of the sky becomes a soughtafter symbol.

连接地面的要求和建筑物的上部结构的结合,使 帕拉第奥 产生了著名的乡村别墅三分法。底层有服务设施,有富丽堂皇的房间和带卧室的阁楼;功能和形式结合在一个连贯的建筑概念中。

The combination of the requirements of the junction with the ground and the upper conclusion of buildings led Palladio to the famous tripartite division of his country villas. The base with the services, the ‘piano nobile’ with the stately rooms and the attic storey with the bedrooms; utility and form combine in one coherent architectural concept.

弱化的边角

凹进去的角落是一种通过清晰地将它们彼此分开来强调立面连接的方法。然后它们以或多或少的自主元素的形式出现。凹槽的重要性表明了外立面的厚度或可居住深度。

The recessed corner is one method of emphasizing the junction of the façades by clearly separating them from each other. They then appear as more or less autonomous elements. The importance of the recess gives an indication of the thickness or habitable depth of the façades.

在文艺复兴时期,当两个壁柱形成了一个角落而没有真正转动它的时候,这种朝向内部的角落的倒置已经被使用了。每个壁柱都属于一个立面,但终端壁柱的概念比负角的概念更进一步。事实上,在20世纪,许多人重新考虑了角的“缺失”。这可能与两种现象有关:首先,立面已经变成非承重的,失去了它的材料厚度;表面的厚度变成了一个选择的问题:密斯·凡·德·罗表达了建筑,而 路易斯·康则使其产生了一种意图。其次,受现代艺术启发的设计引入了角的错位原则,使捆捆的虚拟延伸超出了它们的实际限制,或使形成角的两面与周围空间的相互渗透。 朱塞普·特拉尼 , 它的背向、阳台在回立面上的轻微投影、凉廊和顶棚作为立面上的上端,毫无疑问是一个最辉煌的例子,这种形式的清晰度的角落。另一个例子是科林·罗在《透明性》一书中以娴熟的方式分析了加歇的斯坦别墅。

This inversion of the corner towards the interior was already used in the Renaissance when two pilasters formed a corner without actually turning it. Each pilaster belongs to one façade, but the idea of a terminal pilaster goes further than that of the negative corner. In fact the articulation of the corner by its ‘absence’ has been reconsidered in the twentieth century by many. This is probably linked to two phenomena: firstly the façade, having become non-loadbearing, has lost its material thickness; the apparent thickness then becomes a question of choice: Mies van der Rohe expresses the construction, whereas Kahn subjects it to an intention arising from the brief. Secondly, designs inspired by modern art introduce the principle of dislocation of the corner in favour of a virtual extension of the fagades beyond their real limits or of an interpenetration of the two faces forming the corner with the surrounding space. Giuseppe Terragni’s Casa Frigerio at Como, with its set-backs, the slight projection of the balconies on the return façade and the loggia and canopy as the upper termination on only one of the façades, is without any doubt one of the most brilliant examples of this form of articulation of corner and cornice (Figure 140). Another example is the Villa Stein at Garches analysed in masterly fashion by Colin Rowe and Robert Slutzky in ‘Transparency’.

在20世纪流行的不仅仅是对角落的负面表达或错位:勒·柯布西耶明确地宣称,底层架空是他的现代建筑五点美学原则之一。这个基础被一个空洞代替,有时候这个空洞被“放置”在一个基础上,就像密斯·凡·德·罗的建筑一样。这座建筑盘旋在地面之上,显然与地面分离开来。空间和架空作为建筑和地面之间的中介。

It is not only negative articulation or dislocation of the corner which is popular in the twentieth century: building on pilotis is explicitly pronounced by Le Corbusier to be one of the aesthetic principles amongst his five points of modern architecture. The base is replaced by a void and sometimes this void is, in its turn, ‘placed’ on a base, as in the buildings of Mies van der Rohe. The building hovers above the ground, clearly detaching itself from it. The void and the pilotis act as intermediary between building and ground.

例如,在意大利北部,墙和屋顶之间的负连接已经应用了几个世纪。石墙和木框这两种建筑系统的结合,为屋顶下的楼层提供了不同的用途(晾干食物和衣物、通风阁楼、卧室)(图141)。

Negative articulation between wall and roof has been applied for centuries in northern Italy, for example. The junction of two systems of construction, stone wall and timber frame, provides the opportunity for a different use of the storey under the roof (drying of foodstuffs and laundry, ventilated attics, bedrooms) (Figure 141).

锋利的边角

对传统的拒绝,如角落的浮雕,基座,飞檐和装饰,以及现代运动对基本几何的追求,导致了体积的减少,以最简单的表达。角和胸墙是由两个平面相交产生的线条抽象而成,或由金属边饰投射出精细的金银丝阴影。在帕拉第奥的一些别墅中,角元素的缺失也可以看到,当它们没有覆盖整个房子宽度的山形墙时,但角落仍然强调了窗户的组成和基地的回报。密斯·凡·德·罗是建筑细部棱角衔接的大师,但他的精妙之处从近处看要比从远处看更明显。在20世纪的简单性明显体积不仅是提升到美学美德,结果也从建设呈现砖的方法或采用骨架结构的原则,这使得它可以去除表面的承载功能。从立面仅仅成为一个围护结构的那一刻起——例如幕墙——角落和檐口就不再需要同样的坚固性。根据目前的热需求,无论是否承重,无论新材料还是传统材料,立面几乎总是“包层”。这种建筑方法将影响未来建筑物的外观;“包裹”的概念导致尖锐的边缘或连续性;在没有建筑基础的情况下,连接成为一种奢侈或装饰性的特征。

The rejection of classical conventions, such as the corner in relief, the plinth, cornice and ornament in general, and the search for elementary geometries by the Modern Movement, have led to the reduction of volumes to their simplest expression. The corner and the parapet are defined by the abstraction of a line produced by the meeting of two planes, or the fine filigree of shadow cast by metal trim. The absence of a corner element can also be seen in some of Palladio’s villas when they are not capped by a pediment extending over the whole width of the house, but the corner is emphasized nevertheless by the composition of the windows and the returns of the base. Mies van der Rohe is a master of articulation of the corners of thin façades, but his subtleties are more perceptible from close to than from a distance. In the twentieth century the simplicity of apparent volume is not only elevated to an aesthetic virtue, it also results from the method of construction in rendered brick or from the adoption of the principle of skeleton structure , which makes it possible to remove the load-bearing function from the façade. From the moment when the façade becomes no more than an envelope – a curtain-wall for example – the corner and the cornice no longer need to be of the same solidity. With present thermal requirements the façades are almost always ‘clad’ whether they be load-bearing or not, and whether they be built from new or traditional materials. This method of building will influence the appearance of buildings of the future; the concept of ‘wrapping’ leads to the sharp edge or to continuity; articulation becomes a luxury or a decorative feature without a constructional basis.

墙与地面交界处的尖锐边缘可能给人一种建筑从地面“生长”或“下沉”到地面的印象。这种对地面的渗透可以成为构图的主题,特别是当出现的元素暗示了其他隐藏的元素时,如Pierino Selmoni的巨人雕塑。相反,在阿姆斯特丹或代尔夫特的街道上,作为统一材料的砖块连接着地面和立面。因此,人们有这样一种印象:地面被“折叠”成一堵墙,而建筑的体积似乎并没有延伸到地下。

A sharp edge at the junction of the wall with the ground may give the impression that the building is ‘growing’ from the ground or that it is ‘sinking’ into the ground (Figure 143). This penetration into the ground can become a theme of the composition, especially when the emerging elements suggest other hidden elements as in Pierino Selmoni’s sculpture of the Giant (Figure 144). In the streets of Amsterdam or Delft, on the contrary, brick, used as a unifying material, links the ground and the facades. One thus has the impression that the ground has been ‘folded up’ in order to become a wall, whereas the volume of the building does not seem to extend underground.

边角融合

墙在平面或剖面上的逐渐弯曲会导致物体周围表面的融合。球体是最极端的例子。钝角或圆角,即包络线的连续性而不改变其纹理,也没有断裂的连接,给人一种“体量”的印象。光通过投射一个均匀渐变的阴影来模拟这些物体,并强调它们封闭的形状。要理解这一现象,以维泽莱修道院为例就足够了。它的大桥墩是由一簇簇相互连接的柱子组成的,这些柱子由它们的光和影的多重线条连接而成,看起来并不比内排的半圆形柱子更大,然而,内排的圆柱要细得多。

The gradual bending of a wall on plan or in section causes the fusion of the object’s surrounding surfaces. The sphere is the most extreme example of this. An obtuse or rounded corner, which is to say the continuity of the envelope without change in its texture and without articulation of break, gives an impression of ‘massiveness’. Light models these objects by casting an evenly graded shadow and accentuates their enclosed form. To understand this phenomenon it is sufficient to take the example of the choir of the Abbey of Vézelay. Its large piers, formed from clusters of linked columns articulated by their multiple lines of light and shadow, do not seem any more massive than the round columns of the hemicycle of the inner row which are, nevertheless, much more slender (Figure 145).

毗邻拉土雷特修道院教堂的小教堂是大型建筑的一个例子。没有角落实际上赋予了它比更大的教堂本身更大的“视觉重量”。墙体的倾斜进一步增加了体量的印象,给人一种非常稳定的感觉,让人觉得扎根于地面。因此,这个小建筑的主体获得了从地面突出的岩石的重量。

The chapel adjoining the church of the Convent of La Tourette is an example of the massiveness of an object-building. The absence of corners in fact bestows upon it a greater ‘visual weight’ than on the much larger church itself. The impression of mass is increased still further by the tilting of the walls, which gives rise to a feeling of great stability and of being rooted in the ground. The body of this small building thus acquires the weight of a rock protruding from the ground (Figure 143).

在许多中世纪的城堡和城镇中都出现了地面和物体之间连续性的主题。依附在岩石上,建筑的外形似乎是岩石本身的结晶。既然我们以后不会再回到建筑物的体积或重量的问题上,让我们在这里做一个题外话。角落和开口(门、窗等)的处理构成了一个有用的工具,给人一种“体量”的印象。如果它们像深凹处,它们强调的是巨大。相反,如果窗户与墙面水平,则其表面特征优先于其厚度。开口的相对大小同样决定了质量的性质。在哥特式大教堂中,它接近于建筑被简化成骨架的那一点。相反,相对较小的开口强调体量。

The theme of continuity between ground and object occurs in many medieval castles and towns. Clinging to the rock, the built form appears to be a crystallized excrescence of the rock itself. Since we shall not return later to questions of the massiveness or lightness of buildings, let us make a digression here. The treatment of corners and openings (doors, windows, etc.) constitutes a useful tool for giving an impression of ‘massiveness’. If they resemble deep recesses, they emphasize the massiveness. If, on the contrary, a window is placed level with the face of the wall, its surface character takes precedence over its thickness (Figures 299 and 300). The relative size of the openings is equally decisive for the character of the mass. In Gothic cathedrals it approaches the point at which the construction is reduced to a skeleton. Relatively small openings, on the contrary, emphasize massiveness.

[…] 5.2 独立体的构成:清晰度和连续性 […]