日本的时间与空间 Space-Time in Japan

- 矶崎新 Arata Isozaki

- 1978

A. 神篱 Himorogi

当信徒希望将神召唤到人间时,他们在地上立四个柱子来界定一个方形的神圣区域,神篱。在空间的中心矗立着一根柱子,神明居住在那里,凭代(Yorishiro)和注连绳(Shimenawa)绑在包围这个空间的四个柱子上。正如日本最早定义空间的方式影响了传统的建筑空间构成方法一样,在圣地中放置的白沙和天然石头象征着无穷无尽的力量,也影响了枯山水(Karesansui)的创建。在这些花园中,沙子被用来代表围绕着岩石“岛屿”的“水”。

When worshippers wished to summon kami to earth they prepared a holy place, himorogi, by setting four poles in the earth to mark the comers of a square or rectangle. At the center of the space stood a column where kami dwelled, yorishiro, and a rope (shimenawa) tied around the four posts enclosed this space. Just as this earliest means of defining space in Japan influenced traditional methods of composing architectural spaces, so, too, the white sand and natural stones that were sometimes placed in the holy space to symbolize the numinous forces led to the creation of dry gardens, karesansui. In these unique gardens sand is used to represent the “water”that surrounds “islands”of rock.

B. 桥 Hashi

最初,Hashi 这个词不仅指一座桥,还指边缘、筷子、台阶等。Hashi 这个词并不意味着特定的东西,而是暗示了两个物体之间的的桥接。边缘代表一个世界的极限,假设存在另一个世界。任何越过、填充或投射到鸿沟(两条边界之间)的东西都被称为 Hashi。例如,桥接的“界”可能包括世俗世界和天堂世界;上层和下层;盘子和嘴巴(日语中有一个同音字,意思是筷子,一种在盘子和嘴巴之间的桥接)。登上一座桥敬拜高处的神,用绳索标记边界,登上死亡之船前往海洋之外的天堂,所有这些都是MA的桥接。

Originally the word hashi referred not only to a bridge but also to an edge, chopsticks, steps, etc. The word hashi did not mean a specific thing but rather implied the bridging of MA (space between two objects). An edge represented the limit of one world, assuming the existence of another world beyond. Anything that crossed, filled, or projected into the chasm of MA (space between two edges) was designated hashi. The “edges” bridged might include, for example, the secular world and heavenly world; the upper level and the lower level; the plate and the mouth (there is a homophone hashi in the Japanese language that means chopsticks, an instrument that bridges the MA between the plate and mouth). Ascending a bridge to reach the gods on high, marking boundaries by stretching ropes, embarking on the ship of the dead for the paradise beyond the seas, all these are hashi— the bridging of MA.

C. 暗 Yami

古代日本人认为,被称为Kami的神灵渗透到了整个宇宙中。他们意识到了日光的变化,日光分裂了时间和空间。日光创造了白天和黑夜,创造地球上的生命,也创造了黑暗的世界,Yami。灵魂居住在阴影的世界里,死者的王国;它们在特定时间出现在地球上,然后再次消失在黑暗中。在节日期间,在漆黑的夜晚,供奉着以镜子为象征的神灵的轿子(mikoshi)在火炬游行中被带入村庄。当佛教从中国传入时,一些神道教将神明从黑暗中召唤出来的做法被新宗教所采用。例如,在密教佛教中,守护神被认为从祭坛后面的黑暗中出现。邀请灵魂到人间的仪式后来发展成为公共仪式,后来又在能剧和歌舞伎等复杂的艺术中正式化。因此,在传统的日本戏剧中,演员在舞台上的入口代表了来自冥界的神明的出现。

The ancient Japanese believed that spirits called kami permeated the entire cosmos. They were conscious of the movements of the sun, which divided time and space. The sun created day and night, and life on earth as well as the world of darkness, yami. The spirits dwelt in the world of shadows, the kingdom of the dead; they appeared on earth at specific times, then disappeared again into darkness. At festivals, in the dark of night, the palanquin (mikoshi) that enshrines the kami, symbolized by a mirror, is brought forth into the village in a torchlight procession. When Buddhism was introduced from China some of the Shinto practices of surmmoning the kami from darkness were adopted by the new religion. In Esoteric Buddhism, for example, the guardian deity Fudo-Myoo (Acala) was believed to appear from darkness behind the altar called goma-dan (honma). Rituals performed to invite the spirits to earth later developed into public ceremonies that, still later, were formalized in such sophisticated arts as the Noh drama and the Kabuki. Thus, in the traditional Japanese theater, an actor’s entrance on stage represents the appearance of kami from the underworld.

D. 数寄 Suki

最初,MA的概念表示两点之间的距离。后来,MA发展为一个四面被墙壁包围的空间——一个房间。这种词源演变表明,日本最初的生活空间可能是无墙的,由四个柱子定义的空旷区域。到16世纪末,为了反对武士阶层的家庭建筑的既定风格,人们增加了模仿劳工简易小屋的茶室。这个房间的所有元素都被组装起来,以符合茶艺师的趣味,他也是它的设计师。其中使用和展示的物品是从世界各地收集的,并按照他的意图进行安排。这种不同风格的组成部分的积累构成了一个新世界,一个微观世界。将各种“外国”语言组合在一起的过程很像当时用于创作由古典文本引文组成的新诗的方法,例如和歌(31个音节)和俳句(17个音节)。

Originally the concept of MA expressed the distance between two points. Later MA grew to mean a space surrounded by walls on four sides—a room. This etymological evolution suggests that originally living spaces in Japan may have been wallless, empty zones defined by four posts. Toward the end of the sixteenth century, in a reaction against the established style of domestic building for the warrior class, tea-rooms modeled after the simple huts of laborers were added. All the elements of this room were assembled to suit the taste of the tea master, who was its designer. Articles used and displayed in it were collected from all over the world and arranged as he directed. This accumulation of components of different styles made up a new world, a microcosmos. The process of combining a variety of “foreign” elements was much like the method used at this time in creating new poems made up of quotations from classical texts, as in the waka (31 syllables) and haiku (17 syllables.)

E. 移 Utsuroi

MA 是感知运动瞬间的方式。最初,“Utsuroi”一词的意思是神灵进入并占据空隙的那一刻。(例如,日本人曾经认为圆形石头是空心的,里面住着神灵)。后来,它开始表示神灵的影子从虚空中浮现的那一刻。这种神灵突然出现的感觉深深扎根于日本人的灵魂中,催生了Utsuroi的概念,即大自然转变的时刻,从一种状态过渡到另一种状态。生命的消逝、花朵的枯萎、灵魂的闪烁运动、投射在水和地球上的阴影,这些现象都给日本人留下了深刻的印象。这种对自然的看法反映在建筑空间中,其中平坦、可移动的平面非常薄,以至于透明,一个接一个地放置,控制光线和视线的传输,并产生模糊、不确定的空间。在这样的空间里,光影的闪烁、平面的瞬息万变暗示着自然界的变化,MA是期待着这种变化的瞬间的静止。

MA is the way of sensing the moment of movement. Originally the word utsuroi meant the exact moment when the kami spirit entered into and occupied a vacant space. (For example the Japanese atone time believed that round stones were hollow and were occupied by kami). Later it came to signify the moment when the shadow of the spirit emerged from the void. This sense of kami’s sudden appearance, which is anchored deep in the Japanese soul, gave birth to the idea of utsuroi, the moment when nature is transformed, the passage from one state to another. The fading of life, the wilting of flowers, the flickering movements of the soul, the shadows cast on water and earth are phenomena that have deeply impressed the Japanese. This view of nature is reflected in architectural space where flat, movable planes, so thin as to be transparent, are placed one in front of another, controlling the transmission of light and lines of vision and producing anambiguous, indefinite space. In such a space, the flickering of shadows and the transience of shifting planes allude to the changing world of nature, MA is the expectant stillness of the moment attending this kind of change.

F. 现身 Utsushimi

MA 是人们生活的地方。这里,一位摄影师展示了日本不同地区的各种类型的住房:超级明星的奢华客厅、矿区废弃的小屋、传统农舍、精致的艺伎屋、南方潮湿气候下的草屋、北方地区的泥屋。这张照片记录了我们这些房屋中人们的生活。这些住宅中的房间都被称为 MA。房间地板上的榻榻米数量决定了房间的大小:6 张榻榻米的房间、8 张榻榻米的房间等。这些 MA 中的实际生活方式因气候、社会阶层、知识水平和个人品味而异。MA——人们居住的空间——只有当它带有它所庇护的生活的痕迹时才会对我们产生吸引力。

MA is a place where life is lived. Here a photographer presents different types of housing from various sections of Japan: a superstar’s extravagant living room, a deserted hut in a mining area, a traditional farm house, a sophisticated geisha house, a straw-thatched dwelling in a humid southern climate, a mud house in a northern district. This photographic record shows us how life is Iived in each of these houses. The rooms shown in these dwellings are all called MA. The number of tatami that cover the floor of a room specify its size: a 6-mat room, an 8-mat room, etc. The actual life-style in these MA varies according to climate, social class, intellectual level, and individual taste. MA— the space where people live— becomes attractive to us only when it bears traces of the life it shelters.

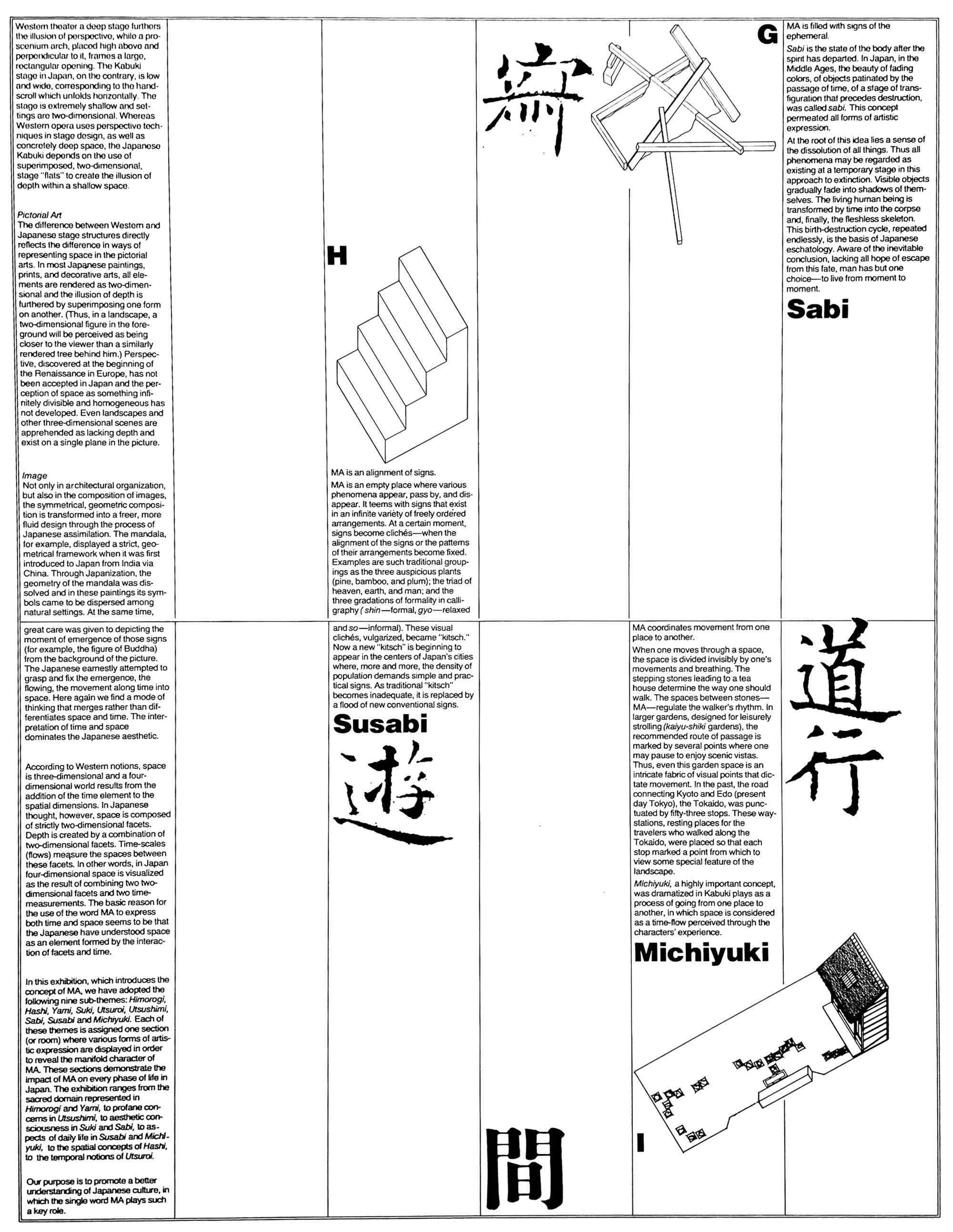

G. 寂 Sabi

MA 充满了短暂的迹象。寂是灵魂离开后身体的状态。在中世纪的日本,褪色的美、随着时间流逝而变色的物体的美、毁灭前的变形阶段的美被称为寂。这一概念渗透到了所有形式的艺术表达中。这一思想的根源在于万物消亡的感觉。因此,所有现象都可以被视为在这种走向灭绝的过程中处于暂时阶段。可见的物体逐渐消失,变成自己的影子。活着的人随着时间的推移变成了尸体,最后变成了没有肉的骷髅。这种生灭循环不断重复,是日本末世论的基础。意识到不可避免的结局,人类对逃脱这一命运毫无希望,只有一个选择——活在当下。

MA is filled with signs of the ephemeral. Sabi is the state of the body after the spirit has departed. In Japan, in the Middle Ages, the beauty of fading colors, of objects patinated by the passage of time, of a stage of trans-figuration that precedes destruction, was called sabi. This concept permeated all forms of artistic expression. At the root of this idea lies a sense of the dissolution of all things. Thus all phenomena may be regarded as existing at a temporary stage in this approach to extinction. Visible objects gradually fade into shadows of themselves. The living human being is transformed by time into the corpse and, finally, the fleshless skeleton. This birth-destruction cycle, repeated endlessly, is the basis of Japanese eschatology. Aware of the inevitable conclusion, lacking all hope of escape from this fate, man has but one choice— to live from moment to moment.

H. 游 Susabi

MA 是符号的排列。MA 是一个空旷的地方,各种现象发生、经过并消失。它充满了以无限多种自由排列方式存在的符号。在某个时刻,符号变成了陈词滥调——当符号的排列或排列模式固定下来时。例如,三种瑞草(松、竹、梅)、天、地、人三合以及书法的三种形式等级(信——正式,行——轻松和非正式)等传统组合。这些视觉陈词滥调被庸俗化,变成了“媚俗”。现在,一种新的“媚俗”开始出现在日本城市的中心,那里的人口密度越来越高,需要简单实用的标志。随着传统“媚俗”变得不够用,它被大量新的传统标志所取代。

MA is an alignment of signs. MA is an empty place where various phenomena appear, pass by, and disappear. It teems with signs that exist in an infinite variety of freely ordered arrangements. At a certain moment, signs become clichés— when the alignment of the signs or the patterns of their arrangements become fixed. Examples are such traditional groupings as the three auspicious plants (pine, bamboo, and plum); the triad of heaven, earth, and man; and the three gradations of formality in calligraphy (shin— formal, gyo— relaxed and so-informal). These visual clichés, vulgarized, became “kitsch.” Now a new “kitsch” is beginning to appear in the centers of Japan’s cities where, more and more, the density of population demands simple and practical signs. As traditional “kitsch” becomes inadequate, it is replaced by a flood of new conventional signs.

I. 道行 Michiyuki

Michiyuki这个词是由两个词组合而成的:MICHI(路)和YUKI(去)。

MA 协调从一个地方到另一个地方的移动。当一个人穿过一个空间时,空间被他的动作和呼吸无形地分割开来。通往茶馆的踏脚石决定了一个人应该走的路。石头之间的空间 MA 调节着步行者的节奏。在专为悠闲漫步而设计的大型花园(回游式花园)中,推荐的通行路线由几个点标记,人们可以在这些点停下来欣赏风景。因此,即使是这个花园空间也是一个复杂的视觉点结构,它们决定着运动。在过去,连接京都和江户(现在的东京)的道路,即东海道,有 53 个站点。这些中途站是沿着东海道行走的旅行者的休息场所,每个站点都标记着一个点,从那里可以看到一些特殊的景观。道行是一个非常重要的概念,在歌舞伎戏剧中被戏剧化为从一个地方到另一个地方的过程,其中空间被视为通过角色的体验感知到的时间流。

The word MICHIYUKI is a combination of two words: MICHI (way) and YUKI (go).

MA coordinates movement from one place to another. When one moves through a space, the space is divided invisibly by one’s movements and breathing. The stepping stones leading to a tea house determine the way one should walk. The spaces between stones MA-regulate the walker’s rhythm. In larger gardens, designed for leisurely strolling (kaiyu-shiki gardens), the recommended route of passage is marked by several points where one may pause to enjoy scenic vistas. Thus, even this garden space is an intricate fabric of visual points that dictate movement. In the past, the road connecting Kyoto and Edo (present day Tokyo), the Tokaido, was punctuated by fifty-three stops. These waystations, resting places for the travelers who walked along the Tokaido, were placed so that each stop marked a point from which to view some special feature of the landscape. Michiyuki, a highly important concept, was dramatized in Kabuki plays as a process of going from one place to another, in which space is considered as a time-flow perceived through the characters’ experience.

[…] 1978 间:日本的时间与空间 MA Space-Time in Japan […]